Chapter 1: Topography shapes the local coexistence of tree species within species complexes of Neotropical forests

Submitted the 7th of April 2020 and under review in Oecologia

Sylvain Schmitt  ,

Niklas Tysklind,

Géraldine Derroire

,

Niklas Tysklind,

Géraldine Derroire  ,

Myriam Heuertz

,

Myriam Heuertz  ,

Bruno Hérault

,

Bruno Hérault

Univ. Bordeaux, INRAE, BIOGECO, 69 route d’Arcachon, 33610 Cestas France; INRAE, UMR EcoFoG (Agroparistech, CNRS, Cirad, Université des Antilles, Université de la Guyane), Campus Agronomique, 97310 Kourou, French Guiana; Cirad, UMR EcoFoG (Agroparistech, CNRS, INRAE, Université des Antilles, Université de la Guyane), Campus Agronomique, 97310 Kourou, French Guiana; CIRAD, UPR Forêts et Sociétés, Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire; Forêts et Sociétés, Univ Montpellier, CIRAD, Montpellier, France; Institut National Polytechnique Félix Houphouët-Boigny, INP-HB, Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire;

Abstract

Lowland Amazonia includes around five thousands described tree species belonging to more than height hundred genera, resulting in many species-rich genera. Numerous species-rich tree genera share a large amount of genetic variation either because of recent common ancestry and/or recurrent hybridization, forming species complexes. Despite the key role that species complexes play in understanding Neotropical diversification, and the need for exploiting a diversity of niches for species complexes to thrive, little is known about local coexistence of Neotropical species complexes in sympatry.

By taking advantage of a study site in a hyperdiverse tropical forest of the Guiana Shield, we explored the fine-scale distribution of five species complexes and 22 species within species complexes across wetness and neighbor crowding gradients representing abiotic and biotic environments respectively. Combining full forest inventories, high-quality botanical determination, and LiDAR-derived topographic data over 120ha of permanent plots, we used a Bayesian modelling framework to test the role of fine-scale topography and tree neighbourhood on the presence of species complexes and the relative distribution of species within complexes.

Species complexes of Neotropical trees were widely spread across topography at the local-scale. Species within species complexes showed pervasive niche differentiation along topographic position, water accumulation, and competition gradients. Moreover, habitat preferences along topography and competition were coordinated among species within several species complexes: species more tolerant to competition for resources grow in drier and less fertile plateaux and slopes as opposed to wet and fertile bottom-lands, where species less tolerant to competition for resources are more abundant. If supported by at least partial reproductive isolation of species and adaptive introgression at the complex level, our results suggest that both habitat specialisation of species within species complexes and the broad ecological distribution of species complexes might explain the success of these Neotropical species complexes at the regional scale.

Keywords

species distribution; syngameon; habitat specialisation; Paracou

Introduction

Tropical forests shelter the highest level of biodiversity worldwide (Gaston 2000), as already showcased by Connell (1978). Lowland Amazonia includes around 5,000 described tree species belonging to 810 genera (Steege et al. 2013), resulting in many species-rich genera. To understand the processes leading to such diversity, it is pivotal to understand what ecological mechanisms lead to the relative success of these species-rich genera. Among them, many have been shown to have a higher level of genetic polymorphism than species-poor genera, oftentimes sharing haplotypes among species, which is likely related to introgression among congeneric species (Caron et al. 2019). Indeed, interspecific hybrids occur in 16% of genera, and more often so in species-rich genera (Whitney et al. 2010). Hybrids are often sterile or less fertile than their parents, although some survive and reproduce allowing the transfer of adaptive variance across species boundaries (Runemark et al. 2019). Species that are morphologically similar, or have blurry morphological differences, and/or share large amounts of genetic variation due to recent common ancestry and/or hybridization are defined as species complexes (Pernès and Lourd 1984). Species complexes can result from adaptive radiation and segregation among species in the use of environmental variable gradients, through a combination and reshuffling of genetic features among species in hybrid swarms (Seehausen 2004), which may multiply the number of potential ecological niches, in turn reducing competition among the species and helping the species gain reproductive isolation (Runemark et al. 2019). The establishment of a hybrid or derived species requires some degree of reproductive isolation from its progenitors to avoid becoming an evolutionary melting pot. Nevertheless, simulations suggest that low hybridization success among congeneric species promotes coexistence of species in the community by allowing the survival or rare species through hybridisation (Cannon and Lerdau 2015). Furthermore, the way we perceive the role of genetic connectivity among populations and species is quickly changing, where species-specific adaptations may be maintained or even maximised despite high levels of gene flow, especially if selective pressures are spatially and/or temporally variable (Tigano and Friesen 2016). When closely related but distinct species that live in sympatry are connected by limited, but recurrent, interspecific gene flow, they are called a syngameon (Suarez-Gonzalez et al. 2018). Syngameons are particular in that they evolve responding to two contrasting evolutionary pressures, those acting at the species level maximizing species-level adaptations to a niche that reduces competition among species, and those acting at the syngameon level which benefit all constituent species. Syngameons as a whole might thus have a selective advantage, decreasing the overall risk of genus extinction, maximising population size, all the while allowing adaptation of their distinct species to specific niches and reducing competition among species (Cannon and Lerdau 2015). Consequently, and in juxtaposition to other types of species complexes, syngameons are not necessarily a transitional or incipient phase of a process towards complete speciation but may be a highly successful evolutionary status per se (Cannon and Lerdau 2015). In one of the best known syngameons, the European white oak, the constituent species lack private cpDNA haplotypes indicating extensive hybridisation (Petit et al. 2002), but each of its constituent species has unique ecological preferences, including drought and cold tolerance, and adaptation to alkaline soils (Leroy et al. 2019, Cannon and Petit 2019). The maintenance of the different species is orchestrated, in part, by the genes allowing survival in their ecological niche preferences (Leroy et al. 2019).

Similarly, Neotropical tree species show pervasive species-habitat associations (Fine et al. 2004, Esteves and Vicentini 2013). Specifically, congeneric species pairs may have contrasting preferences for topography and soil type (Itoh et al. 2003, Allié et al. 2015, Lan et al. 2016), and sometimes may grow in the same abiotic habitat but segregate according to light access (Yamasaki et al. 2013). Habitat specialization may thus support congeneric species coexistence in sympatry. Among Neotropical congeneric tree species, many share genetic variation (Caron et al. 2019), which leads us to hypothesize that they may operate as syngameons.

Despite the key role of species complexes and syngameons in Neotropical ecology, diversification, and evolution (Pinheiro et al. 2018), little is known of the ecological drivers creating and maintaining diversity within Neotropical species complexes (Baraloto et al. 2012a, Steege et al. 2013, Levi et al. 2019a, Cannon and Petit 2019). Particularly, the generality of niche specialisation to environmental variables among species within species complexes, as a potential driver of speciation and maintenance of species complexes, has not been addressed.

Here, we assessed the relative importance of the abiotic environment and biotic interactions in shaping species distribution within and among species complexes. We took advantage of the Paracou study site with more than 75,000 censused and geolocalized individual trees in a highly diverse tropical forest site located within the Guiana Shield in Amazonia. The Paracou site encompasses a diversity of micro-habitats through topographic variation ranging from seasonally flooded bottomlands to drier plateaus (Gourlet-Fleury et al. 2004) and displays variation in canopy gap size distribution (Goulamoussène et al. 2017) and forest turn-over (Ferry et al. 2010a). Combining tree inventories and LiDAR-derived topographic data, we used Bayesian modelling to address the following questions: (1) Are species complexes widely spread across biotic and abiotic environments, i.e. as generalists, or do they occupy specific niches, i.e. as specialists? (2) Do species within complexes also behave as generalists or does the biotic and abiotic environment favor niche differentiation within species complexes ?

Material and Methods

Study site

The study was conducted in the northernmost part of the Guiana Plateau region, at the Paracou field station. The site is characterized by an average of 3,102 mm annual rainfall and mean air temperature of 25.7°C (Aguilos et al. 2018). Old tropical forest with an exceptional richness (e.g. over 750 woody species) develops in this area across a succession of small hills rising to 10–40 m a.s.l. (Gourlet-Fleury et al. 2004). We used seven undisturbed permanent inventory plots from Paracou (i.e. six plots of 6.25 ha and one of 25 ha) which have been censused (i.e. diameter at breast height > 10 cm) every 1-2 years since 1984.

Species complexes

From the Paracou database, we identified five species complexes based on evidence for low (phylo-)genetic resolution or plastid DNA sharing in the clade (Gonzalez et al. 2009, Baraloto et al. 2012a, Caron et al. 2019): Eschweilera clade Parvifolia (Lecythidaceae; Chave et al. unpublished; Heuertz et al. 2020); Licania (Chrysobalanaceae; Bardon et al. 2016); Iryanthera (Myristicaceae); Symphonia (Clusiaceae; Torroba-Balmori et al. (2017)]; and Talisia (Sapindaceae). We removed species with less than ten individuals in Paracou in 2015, which resulted in five species complexes each including two to nine species (Tab. 1). The species in the five species complexes are dispersed by animals and/or birds (Eschweilera see Mori et al. (1993); Iryanthera see Howe (1983); Licania see Hammond and Brown (1995), Symphonia see Forget et al. (2007); Talisia see Julliot (1996) and Larpin and Larpin (1993)). In addition, Eschweilera, Licania, and Talisia share haplotypes between species pairs (Caron et al. 2019) and Symphonia shows introgression between species pairs (S. Schmitt in prep.), suggesting interspecific gene flow characteristic of syngameons.

| Complex | Genus | Species | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iryanthera | Iryanthera | sagotiana | 381 |

| Iryanthera | Iryanthera | hostmannii | 335 |

| Licania | Licania | alba | 1117 |

| Licania | Licania | membranacea | 442 |

| Licania | Licania | canescens | 164 |

| Licania | Licania | micrantha | 139 |

| Licania | Licania | ovalifolia | 95 |

| Licania | Licania | sprucei | 76 |

| Licania | Licania | laxiflora | 37 |

| Licania | Licania | parvifructa | 12 |

| Licania | Licania | densiflora | 6 |

| Parvifolia | Eschweilera | sagotiana | 1208 |

| Parvifolia | Eschweilera | coriacea | 500 |

| Parvifolia | Eschweilera | decolorans | 84 |

| Parvifolia | Eschweilera | wachenheimii | 19 |

| Parvifolia | Eschweilera | grandiflora | 14 |

| Parvifolia | Eschweilera | pedicellata | 14 |

| Symphonia | Symphonia | sp.1 | 382 |

| Symphonia | Symphonia | globulifera | 71 |

| Talisia | Talisia | hexaphylla | 60 |

| Talisia | Talisia | praealta | 37 |

| Talisia | Talisia | simaboides | 31 |

Environmental variables

Two near-uncorrelated (Pearson’s , see supplementary material Fig. 28) environmental descriptors were chosen to depict the distribution of species complexes and that of species within complexes. Topographic wetness index () identifies water accumulation areas and is thus critical for species distribution at local scale in tropical ecosystems (Ferry et al. 2010a, Allié et al. 2015). was derived from a 1-m resolution digital elevation model built based on data from a LiDAR campaign done in 2015 using SAGA-GIS (Conrad et al. 2015).

A neighbourhood crowding index (NCI; Uriarte et al. 2004b) was calculated from field censuses and used as a descriptor of the biotic interactions among trees. Although we recognize their potential non-negligible role in explaining species distributions, other biotic effects, such as variance in herbivory pressure and pathogen species richness, were not directly included into our analyses. The neighbourhood crowding index for each tree individual was calculated with the following formula:

where is the diameter of neighbouring tree and its distance to individual tree . is computed for neighbours at a distance of up to 20m because showed negligible effect beyond 20m in preliminary analysis. The size effect of neighbours was taken as their squared , and hence proportional to their basal area. The distance effect of neighbours was set to -1/4, corresponding to neighbours beyond 20m having less than 1% effect compared to the effect of neighbours at 0m.

Analyses

Distribution of complexes

The distribution of each species complex was inferred separately. We considered the occurrences of all individuals from species belonging to the species complex as presences, and all occurrences of trees belonging to other species as pseudo-absences. The presence of each species complex Presencespecies complexk was inferred with a logistic regression within a Bernoulli distribution (which corresponds to the best model form among several forms tested, see supplementary material Tab. 6 and Fig. 29):

were is the matrix of environmental descriptors ( and ), is the intercept, is a vector representing the slope of environmental descriptors and is a vector representing the quadratic form of effects of environmental descriptors for every species complex .

Distribution of species

Joint distributions of species were inferred within each species complex. We used a softmax regression within a conjugated Dirichlet Process and Multinomial distribution:

were represents the species for every individual as a simplex of 0s and 1s (i.e. 0 for all other species from the species complex and 1 for the considered species), is the matrix of environmental descriptors (i.e. and ), is the vector of species intercepts, is a matrix representing the slope of environmental descriptors and is a matrix representing the quadratic form of effects of environmental descriptor for every species iof the species complex .

Environmental descriptors were all reduced in order to ease model inference and compare the strength of the effects among environmental descriptors. A Bayesian method was used to infer parameters of all models using stan language (Carpenter et al. 2017, see supplementary material Species complex code and Species code) and rstan package (Stan Development Team 2018) in the R environment (R Core Team 2020).

Results

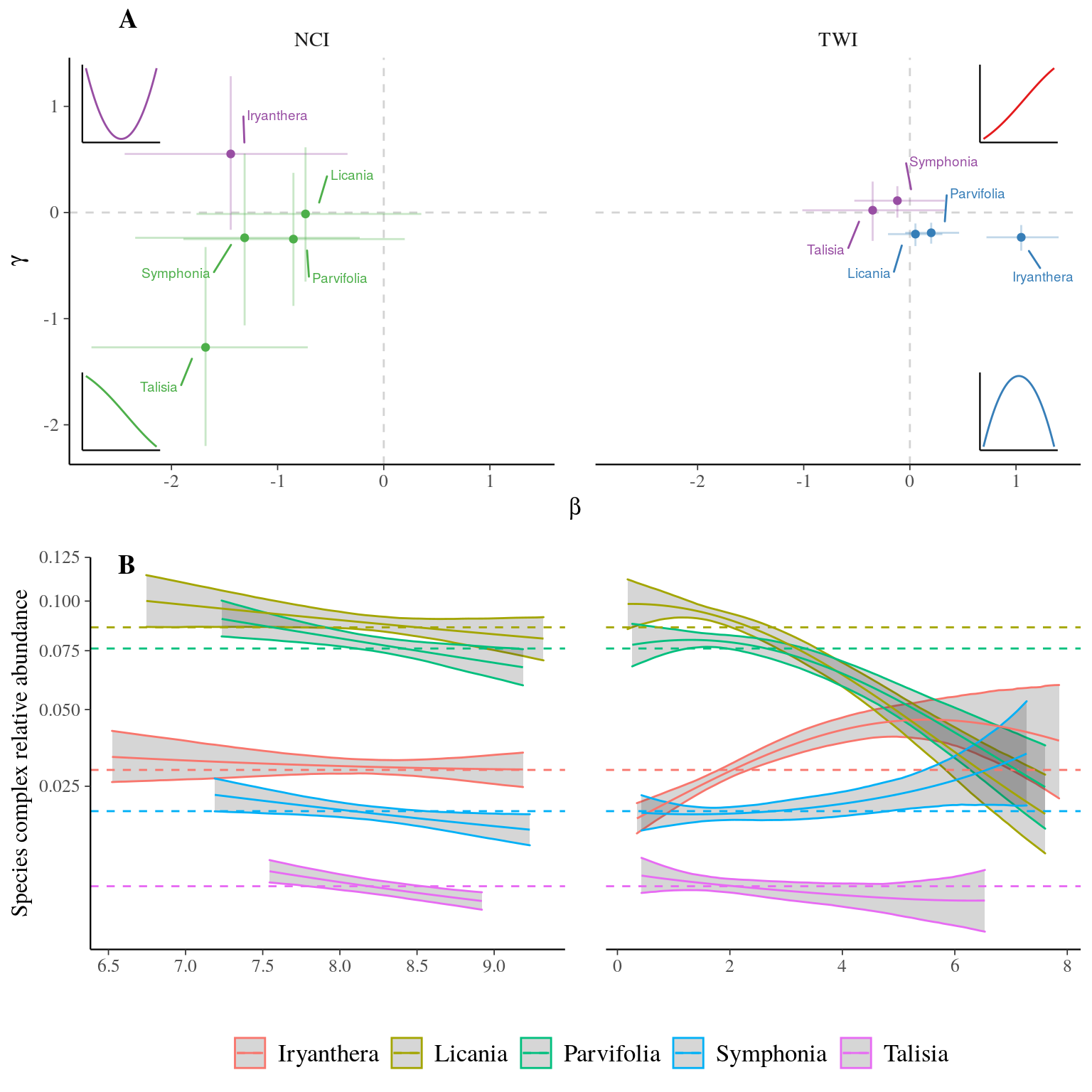

The topographic wetness index () and the neighbourhood crowding index () had globally null or weak effects on the abundance of species complexes, at the exception of an effect of TWI on Eschweilera clade Parvifolia, Licania, and Iryanthera (Fig. 2). Wet habitats () resulted in increased abundance of the species complexe Iryanthera but a decreased abundance of the species complexes Licania and Eschweilera clade Parvifolia (Fig. 1B). Despite did not change species complex ranking in abundance.

Figure 2: Parameters posteriors (A) and predicted relative abundance (B) for species complexes. Subplot A represent parameters posteriors for species complexes as their position in the - space for each descriptor ( and ), with the point representing the mean value of the parameter posterior, thin lines the 80% confidence interval. The color indicates the sign of anddetermining the shape of the distribution represented by the 4 subplots with corresponding colors. Subplot B, represent species complex predicted relative abundance with solid line and area representing respectively the mean and the 95% confidence interval of projected relative abundance of species complexes depending on descriptors. The color indicates the species complex whereas the dashed lines represent the mean relative abundance of the complex in Paracou.

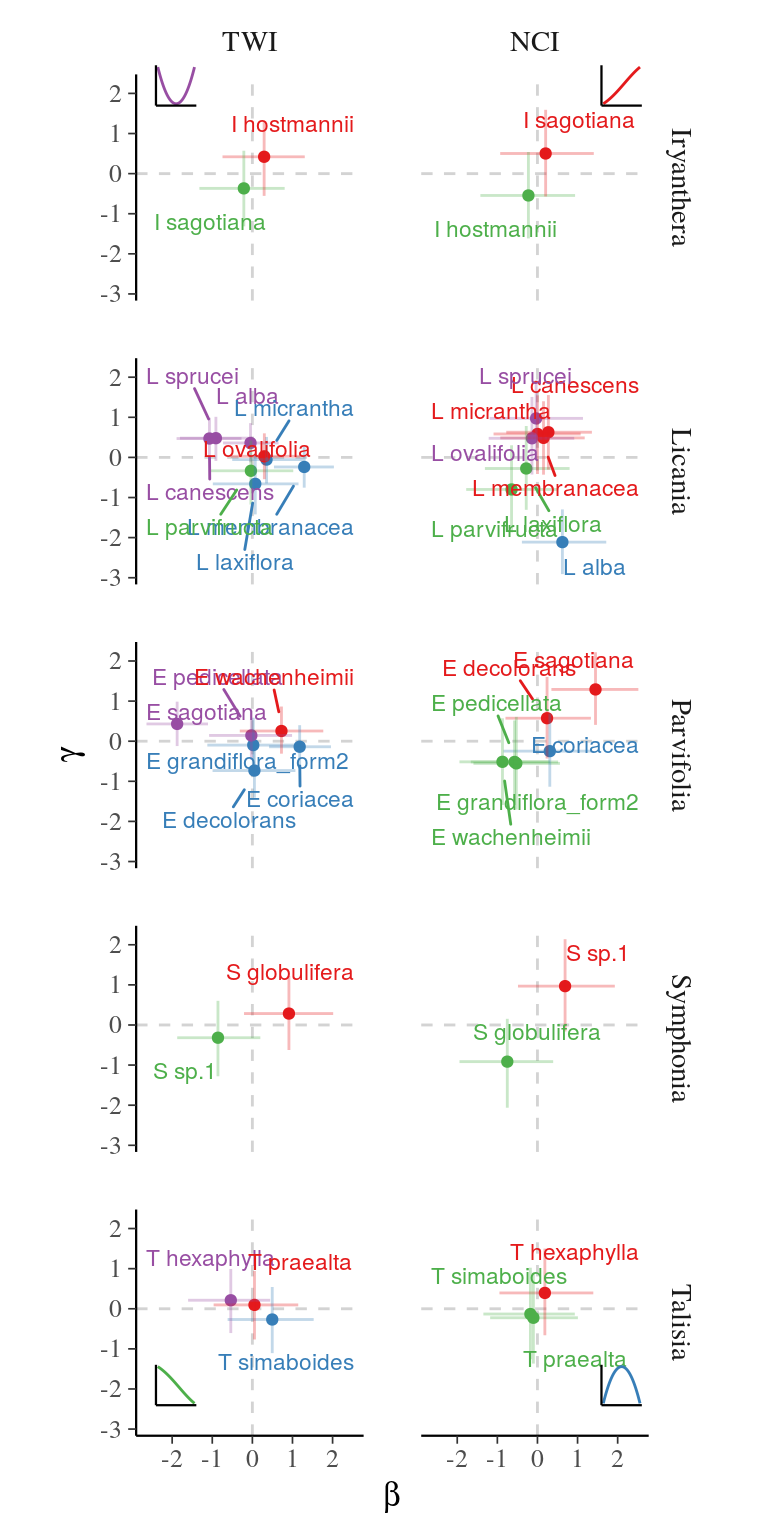

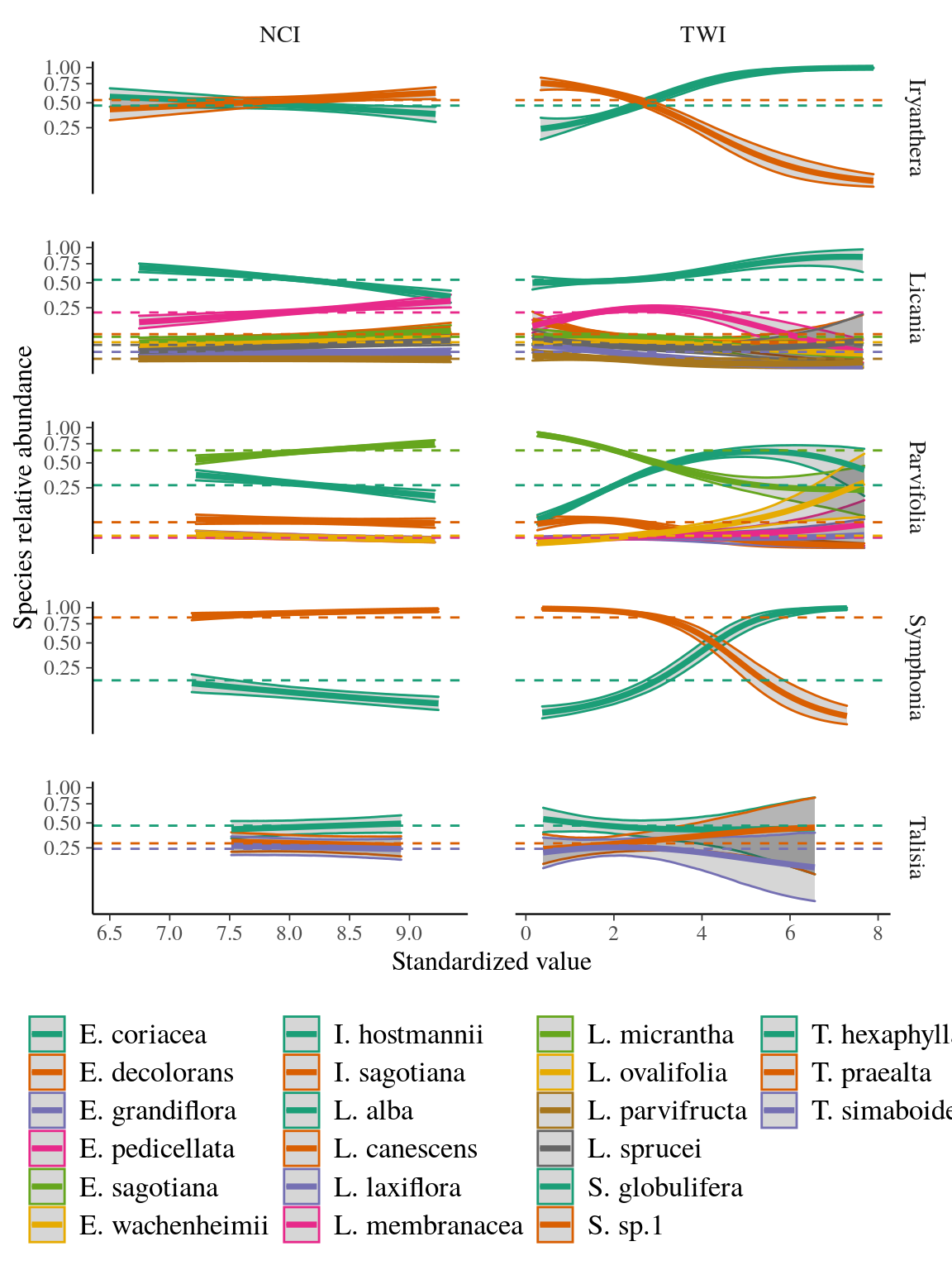

Conversely, the strongly influenced the species distribution within complexes with a shift in species dominance, while the effect of the was substantial but did not shift species dominance within species complex. and effects are illustrated by a gradient of response from positive and parameters (i.e. increasing curve) to negative and parameters (i.e. decreasing curve) within each complex, besides a few positive-negative associations of parameters indicating a bell curve with a local extremum (Fig. 3). For instance, I. hostmanii, E. coriacea, and S. globulifera species relative abundances increased with water accumulation () when it decreased for I. sagotiana, E. sagotiana, and S. sp1 within Iryanthera, Eschweilera clade Parvifolia and Symphonia species complexes respectively (Fig. 4). The change of relative abundance along the topography gradient even led to a shift of dominance between aforementioned species within Symphonia, Eschweilera clade Parvifolia and Iryanthera species complexes, revealing a strong effect of topography. Similarly, L. membranacea, E. sagotiana, and S. sp1 species relative abundances increased with neighbour crowding () when it decreased for L. alba, E. coriacea, and S. globulifera within Licania, Eschweilera clade Parvifolia and Symphonia species complexes respectively (Fig. 4). Thus, two species complexes included species with opposed preference of and . For instance, S. sp1 more tolerant to neighbor crowding grow preferentially in drier habitats such as plateaux when S. globulifera is more abundant with decreased neighbor crowding and dominates in wet habitat such as bottom-lands.

Figure 3: and effects on species relative distribution within species complexes. Parameters posteriors for species within species complexes is represented as their position in the - space for each descriptor and each complex, with the point representing the mean value of the parameter posterior, thin lines the 80% confidence interval. The color indicates the sign of anddetermining the shape of the distribution represented by the 4 subplots with corresponding colors.

Figure 4: Relative abundance of species within species complexes. Predicted relative abundance of species within species complexes with dashed line indicating observed relative abundance of species within species complex in Paracou, and solid line and area representing respectively the mean and the 95% confidence interval of projected relative abundance of species complexes depending on descriptors. The color indicates the species complex.

Discussion

Understanding the the eco-evolutionary processes creating and maintaining species complexes, such as how species within species complexes segregate in their ecological niche exploitation (Runemark et al. 2019), is paramount to further our knowledge of Neotropical diversification processes (Pinheiro et al. 2018). Nevertheless, the ecological processes governing species complexes distributions in the Neotropics have received relatively little attention (Baraloto et al. 2012b, Steege et al. 2013, Levi et al. 2019a). Here, we show that species complexes of Neotropical trees as a whole span all the topography and competition gradients and are thus widely spread across light, water, and nutrient habitats at fine-scale. Conversely, most species within species complexes show pervasive niche differentiation along topographic position, water accumulation, and competition gradients. Habitat preferences along topography and competition were coordinated among species within several species complexes: species more tolerant to competition for resources grow in drier and less fertile plateaux and slopes as opposed to wet and fertile bottom-lands, where species less tolerant to competition for resources are more frequently found. Consequently, if supported by as least partial ecological reproductive isolation of species, but with occasional adaptive introgression at the complex level, our results suggest that both widespread distribution of species complexes combined with habitat specialisation of species within species complex might explain the success of these Neotropical species complexes at the regional scale (Steege et al. 2013).

Species complexes are widely spread across habitats

The general null or weak effects of biotic and abiotic environmental variables considered here on species complexes distribution suggest that species complexes are widely spread across light, water, and nutrient habitats at the local-scale, and that the species complexes are capable of exploiting the whole range of environmental conditions studied here, supporting our hypothesis of widespread species complexes at the local scale. Topographic wetness index () indicates the topographic position where water accumulates. Neighbourhood crowding index () represents competition with neighbours and thus access to light, water, and nutrients. Consequently, and represent the combined effects of abiotic and biotic environment in defining local scale habitats for species and species complexes distributions. In our study, and had no effect on species complexes distribution, at the exception of a weak effect of on Iryanthera, Licania, and Eschweilera clade Parvifolia abundances, emphasizing the generality of the widespread distribution of species complexes across local habitats. In a nutshell, species complexes span the whole light, water, and nutrients gradients with either segregated species with ecological preferences or generalist species.

The higher abundance of Iryanthera species complex in wet habitats has been already evidenced experimentally (Baraloto et al. 2007). Species complexes increased or decreased abundance at high values might be due to variations in species complex-specific adaptations to a more constraining habitat such as anoxia.

Species show pervasive niche differentiation within species complexes

The repeated opposed response of species relative distribution within species complexes to biotic and abiotic environments showed a pervasive niche differentiation of species within four locally abundant species complexes. Indeed, species within Iryanthera, Licania, Symphonia, and Eschweilera clade Parvifolia species complexes are segregated along a gradient from wet to drier habitats and a gradient from low crowding to increased crowding.

Habitat segregation along topography and wetness gradients correspond to the well known bottomland to plateau gradient observed in Amazonia (Kraft et al. 2008, Ferry et al. 2010a). Species within species complexes segregate between seasonally flooded habitats resulting in anoxia but increased soil fertility and drier habitats more susceptible to suffering from drought and reduced fertility, besides few species growing preferentially in intermediate habitat (e.g. Licania membranacea, Fig. 3). Indeed, water-use strategies and edaphic conditions shape divergent habitat associations between congeneric species pairs (Baltzer et al. 2005). Our results are in agreement with previous evidence of species-habitat association with topography between sympatric congeneric species at local scale (Itoh et al. 2003, Allié et al. 2015, Lan et al. 2016, but see Baldeck et al. 2013a). But, we tested topography in our study but not edaphic properties. Besides covariation with topography, edaphic properties have independent effect on the species distribution (Baldeck et al. 2013b), which may increase species niche differentiation within species complexes.

Moreover, species within species complexes segregate also between high crowding resulting in decreased access to light, water, and nutrients and low neighboring with less competition for resources. (Yamasaki et al. 2013) already evidenced segregation with light access between two congeneric species at local scale, but growing in the same topography. In our study, at least four species showed more tolerance to competition for resources (i.e. high ) and grow in drier and less fertile habitats (i.e. low ), whereas species growing in wet habitats also grow preferentially with less competition for resources.

Conclusion

We found Neotropical tree species complexes to be widespread across habitats at local scale, while the species composing them showed pervasive habitat differentiation along topography and competition gradients. The pervasive niche differentiation among species within species complex might be related to repeated functional strategy adaptation to local environment (Baltzer et al. 2005, Baraloto et al. 2007) with several diversification events across taxa (e.g. (Fine et al. 2004) for Protiae). Habitat specialisation reduces competition among the species and thus helps the species gain reproductive isolation for their establishment within species complex (Runemark et al. 2019), especially in our study for animal dispersed species with reduced dispersion. Meanwhile, porous genomes allow for the transfer of adaptive genes through introgression that may benefit one or several species, allowing coevolution at the species complex level (Cannon and Lerdau 2015). Consequently, if habitat specialisation allow at least partial reproductive isolation and porous genomes allow adaptive introgression, our results suggest that both habitat specialisation of species within species complex and widespread distribution of species complexes might explain the success of these Neotropical species complex at the regional scale (Steege et al. 2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Bordeaux for a PhD grant to Sylvain Schmitt. We are grateful to Pascal Petronelli and the CIRAD inventory team for their work on tree inventories and botanical identification. This study was partially funded by an Investissement d’Avenir grant of the ANR: CEBA (ANR-10-LABEX-0025).

Data accessibility

TWI and spatial positions of individuals were extracted from the Paracou Station database, for which access is modulated by the scientific director of the station (https://paracou.cirad.fr).

References

Aguilos, M. et al. 2018. Interannual and Seasonal Variations in Ecosystem Transpiration and Water Use Efficiency in a Tropical Rainforest. - Forests 10: 14.

Allié, E. et al. 2015. Pervasive local-scale tree-soil habitat association in a tropical forest community. - PLoS ONE 10: e0141488.

Baldeck, C. A. et al. 2013a. A taxonomic comparison of local habitat niches of tropical trees. - Oecologia 173: 1491–1498.

Baldeck, C. A. et al. 2013b. Soil resources and topography shape local tree community structure in tropical forests. - Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences in press.

Baltzer, J. L. et al. 2005. Edaphic specialization in tropical trees: Physiological correlates and responses to reciprocal transplantation. - Ecology 86: 3063–3077.

Baraloto, C. et al. 2007. Seasonal water stress tolerance and habitat associations within four Neotropical tree genera. - Ecology 88: 478–489.

Baraloto, C. et al. 2012a. Using functional traits and phylogenetic trees to examine the assembly of tropical tree communities. - Journal of Ecology 100: 690–701.

Baraloto, C. et al. 2012b. Contrasting taxonomic and functional responses of a tropical tree community to selective logging. - Journal of Applied Ecology 49: 861–870.

Bardon, L. et al. 2016. Unraveling the biogeographical history of chrysobalanaceae from plastid genomes. - American Journal of Botany 103: 1089–1102.

Cannon, C. H. and Lerdau, M. 2015. Variable mating behaviors and the maintenance of tropical biodiversity. - Frontiers in Genetics 6: 183.

Cannon, C. H. and Petit, R. J. 2019. The oak syngameon: more than the sum of its parts. - New Phytologist: nph.16091.

Caron, H. et al. 2019. Chloroplast DNA variation in a hyperdiverse tropical tree community. - Ecology and Evolution 9: ece3.5096.

Carpenter, B. et al. 2017. Stan : A Probabilistic Programming Language. - Journal of Statistical Software in press.

Connell, J. H. 1978. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. - Science 199: 1302–1310.

Conrad, O. et al. 2015. System for Automated Geoscientific Analyses (SAGA) v. 2.1.4. - Geoscientific Model Development 8: 1991–2007.

Esteves, S. de M. and Vicentini, A. 2013. Cryptic species in Pagamea coriacea sensu lato (Rubiaceae): evidence from morphology, ecology and reproductive behavior in a sympatric context. - Acta Amazonica 43: 415–428.

Ferry, B. et al. 2010a. Higher treefall rates on slopes and waterlogged soils result in lower stand biomass and productivity in a tropical rain forest. - Journal of Ecology 98: 106–116.

Fine, P. V. A. et al. 2004. Herbivores promote habitat specialization by trees in Amazonian forests. - Science (New York, N.Y.) 305: 663–5.

Forget, P. et al. 2007. Seed allometry and disperser assemblages in tropical rainforests: a comparison of four floras on different continents. - In: Dennis, A. et al. (eds), Seed dispersal theory and its application in a changing world. ppp. 5–36.

Gaston, K. J. 2000. Global patterns in biodiversity. - Nature 405: 220–227.

Gonzalez, M. A. et al. 2009. Identification of amazonian trees with DNA barcodes. - PLoS ONE 4: e7483.

Goulamoussène, Y. et al. 2017. Environmental control of natural gap size distribution in tropical forests. - Biogeosciences 14: 353–364.

Gourlet-Fleury, S. et al. 2004. Ecology and management of a neotropical rainforest : lessons drawn from Paracou, a long-term experimental research site in French Guiana Ecology and management of a neotropical rainforest : lessons drawn from Paracou, a long-term experimental research sit. - Paris: Elsevier.

Hammond, D. S. and Brown, V. K. 1995. Seed Size of Woody Plants in Relation to Disturbance, Dispersal, Soil Type in Wet Neotropical Forests. - Ecology 76: 2544–2561.

Heuertz, M. et al. 2020. The hyperdominant tropical tree Eschweilera coriacea (Parvifolia clade, Lecythidaceae) shows higher genetic heterogeneity than sympatric Eschweilera species in French Guiana. - Plant Ecology and Evolution. 153: 67–81.

Howe, H. 1983. Annual variation in a neotropical seed-dispersal system. - In: Sutton, S. et al. (eds), Tropical rain forests: Ecology and management. Blackwell, Oxford, UK., ppp. 211–227.

Itoh, A. et al. 2003. Importance of topography and soil texture in the spatial distribution of two sympatric dipterocarp trees in a Bornean rainforest. - Ecological Research 18: 307–320.

Julliot, C. 1996. Fruit choice by red howler monkeys (Alouatta seniculus) in a tropical rain forest. - American Journal of Primatology 40: 261–282.

Kraft, N. J. B. et al. 2008. Functional traits and niche-based tree community assembly in an Amazonian forest. - Science 322: 580–582.

Lan, G. et al. 2016. Species associations of congeneric species in a tropical seasonal rain forest of China. - Journal of Tropical Ecology 32: 201–212.

Larpin, D. and Larpin, D. 1993. Seed dispersal and vegetation dynamics at a cock-of-the-rock’s lek in the tropical forest of French Guiana. - Journal of Tropical Ecology 9: 109–116.

Leroy, T. et al. 2019. Massive postglacial gene flow between European white oaks uncovered genes underlying species barriers. - New Phytologist in press.

Levi, T. et al. 2019a. Tropical forests can maintain hyperdiversity because of enemies. - Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116: 581–586.

Mori, S. A. et al. 1993. Flora of the Guianas: Phanerogams. 53. Lecythidaceae, including Wood and Timber. Series A. Fascicle 12.

Pernès, J. and Lourd, M. 1984. Organisation des complexes d’espèces. - Gestion de ressources genetiques des plantes in press.

Petit, R. J. et al. 2002. Identification of refugia and post-glacial colonisation routes of European white oaks based on chloroplast DNA and fossil pollen evidence. - Forest Ecology and Management 156: 49–74.

Pinheiro, F. et al. 2018. Plant Species Complexes as Models to Understand Speciation and Evolution: A Review of South American Studies. - Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 37: 54–80.

R Core Team 2020. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing.

Runemark, A. et al. 2019. Eukaryote hybrid genomes. - PLOS Genetics 15: e1008404.

Seehausen, O. 2004. Hybridization and adaptive radiation. - Trends in Ecology & Evolution 19: 198–207.

Stan Development Team 2018. Rstan: the R interface to Stan.

Steege, H. ter et al. 2013. Hyperdominance in the Amazonian Tree Flora. - Science 342: 1243092–1243092.

Tigano, A. and Friesen, V. L. 2016. Genomics of local adaptation with gene flow. - Molecular Ecology 25: 2144–2164.

Torroba-Balmori, P. et al. 2017. Altitudinal gradients, biogeographic history and microhabitat adaptation affect fine-scale spatial genetic structure in African and Neotropical populations of an ancient tropical tree species. - PLOS ONE 12: e0182515.

Uriarte, M. et al. 2004b. A neighborhood analysis of tree growth and survival in a hurricane-driven tropical forest. - Ecological Monographs 74: 591–614.

Whitney, K. D. et al. 2010. Patterns of hybridization in plants. - Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 12: 175–182.

Yamasaki, N. et al. 2013. Coexistence of two congeneric tree species of Lauraceae in a secondary warm-temperate forest on Miyajima Island, south-western Japan. - Plant Species Biology 28: 41–50.